School funding: promised increases are actually real-term cuts – and poorer schools are hit hardest

Recent changes to school funding in England mean that, although there may seem to be more money for education, in general schools will be worse off in 2021 than they have been over the last few years. In the second half of 2019, the government announced a £14 billion increase in funding for schools in England. This is over three years: £2.6 billion in 2020-21, increasing to £4.8 billion in 2021-22 and £7.1 billion in 2022-23. The National Education Union (NEU) analysed the figures, and despite the cash injection, found “a strong link between deprivation and the scale of government cuts to school funding”. The NEU suggests that, when inflation is taken into account, over 16,000 schools will have less income in April 2020, compared to 2015. Over the past decade, school spending per pupil in the UK has fallen by about 8% in real terms. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, this is the largest decline since at least the 1970s. For historical reasons to do with how funding used to be calculated, these cuts will hit schools in the most disadvantaged areas hard. Feeling the effectsChildren in classrooms – particularly in disadvantaged areas – are already feeling the very real effects of funding cuts. Staff are being made redundant, schools have fewer resources, and some schools are even considering closing for half a day per week to save money. Recent apparent funding increases are in fact real-term cuts – and teachers and parents are rightly concerned. In April, a survey of 8,600 teachers and other school staff conducted by the National Education Union found that 91% of teachers felt that poverty was a factor in limiting children’s capacity to learn. Three-quarters of those surveyed blamed poverty for children falling asleep during lessons, being unable to concentrate and behaving badly.

Many teachers in schools face these problems every day, while also having to handle issues that arise as a result of austerity and cutbacks to other services, such as health and social care. As a result, nearly half (45%) of teachers surveyed said that they have spent their own money buying basic necessities for pupils in the last year. Yet current government policy does nothing to level the playing field in terms of structural inequalities: in fact, it reinforces them. A complex systemSchool funding in England is complicated, partly because there are so many kinds of schools – between 70 and 90, on one estimate – and partly because the mechanisms change quite often. It’s also complex because there are so many rules, depending on whether pupils are certain ages, or have special educational needs. In general, however, people tend to have two key concerns: how much money is going into schools from the government, and whether this money is being distributed fairly. All children in England between the ages of five and 16 are entitled to a free place at a state school. There were nearly 9m children in English schools in January 2019: about half of the pupils in state-funded schools in England are in maintained schools, and about half in academies and free schools. Maintained schools are so called because they are funded and controlled by the local authority. Maintained schools must follow the national curriculum and other rules, for example about teachers’ pay and conditions. Academies and free schools are state-funded, non-fee-paying schools, which are are independent of local authorities and operate outside of their control. These schools are run by trusts or sponsors such as parents’ groups or businesses. They still get funding from the government, but they can decide how to spend their budget themselves, and they can set their own entrance criteria. A 2013 report by the Academies Commission stated that it received evidence of some popular schools, including academies, attempting to select and exclude certain pupils; there tends to be a decrease in the proportion of disadvantaged pupils enrolling in academies, and a resultant increase in intakes in maintained schools. The fact that academies set their own admissions policies “attracted controversy and fuelled concerns that the growth of academies may entrench rather than mitigate social inequalities”, according to the report. Fair funding?The National Funding Formula (NFF) is the formula that is used to allocate school funding. This is a basic per-pupil funding allocation, and then there are adjustments for things like additional needs. The NFF is used to calculate funding for individual schools, and then the total for an area is calculated and the amount passed on to the local authority. Councils then set their own formula, in agreement with school forums made up of head teachers, to distribute the cash. The formula must include both a basic local funding unit for each pupil attending the school, and a measure of deprivation. It can also take into consideration some other elements, such as the number of pupils with English as an additional language. Academy funding comes directly from the Department for Education (DfE); local authorities instruct the DfE how much to pay each academy in their area. This is all quite likely to change, though – and then it is possible that NFF funding will be paid directly to all mainstream schools. Another important source of funding for schools is the pupil premium, which was introduced by the government in 2011. The amount is allocated based on the number of pupils who are or have been eligible for free school meals, and also those who have parents in the armed forces, and intended to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. Schools are accountable for how they spend the pupil premium, but they don’t have to spend it just on eligible pupils. So the question remains: why are measures such as pupil premium and the national funding formula failing to level the playing field? Rising costsIn July 2019, the Education Select Committee reported that it was clear that pupil premium was not always directed at disadvantaged children – rather, it is often used to make up shortfalls in school budgets. As the select committee noted, schools should not have to choose between running their core operations and supporting disadvantaged pupils. The fact that this is happening shows that there is simply not enough money in the school funding system. School costs have increased across a range of areas, including annual pay award and salary raises, inflation, pensions and special educational needs provision. School funding has not kept pace. Jon Andrews, director for school system and performance at the Education Policy Institute think-tank, said that the government’s policies on education funding “target money towards schools with less challenging intakes and lower levels of disadvantage – at a time when progress in closing the gap between disadvantage pupils and their peers has stalled”. Promised increases to funding are likely to be real-term cuts. Schools and children are suffering because of inequitable policies – and this will have far-reaching consequences for the economy and wider society, long into the future. Janet Lord, Faculty Head of Education, Manchester Metropolitan University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

1 Comment

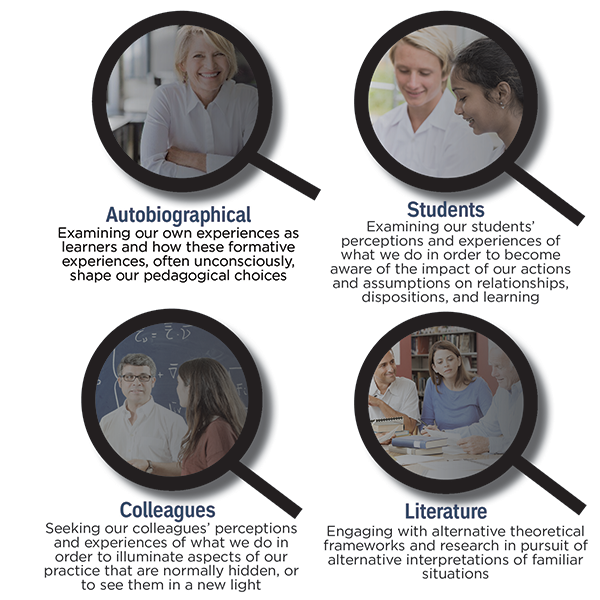

I've just had a case study accepted for the second edition of Peter Kahn and Lorraine Walsh's book on 'Developing your teaching'. I'm really pleased! I wrote it about reflective practice, and how I use Brookfield's lenses and reflective journals in my own work. It reflects my approach to teaching social justice. But in writing it, and in correspondence with Lorraine about my work, I realised that I don't give enough time to thinking about how I reflect; at least not in terms if pedagogy- should the reflection 'match' or be linked to the pedagogy or subject matter. And I also haven't formalized the ideas about how I decide which teaching methods I use in which sessions, and why. So then I started to think about how you could deconstruct pedagogy - what are the features (possibly, what are the outcomes) of effective pedagogy? The Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence at the University of California talks about these being key aspects: joint productive activity; language development; contextualization; challenging activities; and Instructional Conversation (IC). https://www.tolerance.org/professional-development/five-standards-of-effective-pedagogy In 2012 Chris Husbands and Jo Pearce wrote a booklet for the National College; What makes great pedagogy? Nine claims from research. They conclude: This review has set out nine claims about what makes for great pedagogic practices drawing on a range of research evidence. The evidence which has been reviewed suggests that outstanding pedagogy is far from straightforward. Classrooms are complex, multi-faceted and demanding places in which to work and successful pedagogies are correspondingly sophisticated. Highly successful pedagogies develop when teachers make outstanding use of their understanding of the research and knowledge-base for teaching in order to support high-quality planning and practice. The very best teaching arises when this research base is supplemented by a personal passion for what is to be taught and for the aspirations of learners. There is a robust evidence base which helps to identify the ingredients of outstanding pedagogic practices. However, truly effective practices depend on teachers making active connections between the ideas from research. The most effective successful classroom practices work these ideas together in systematic and sophisticated ways, and the best teachers are active in building relationships between them. Understanding the ways in which these relationships are built – what Leahy et al (2005) have called ‘minute-by-minute classroom practices’ – is itself a fruitful area for both further research and improving practice. And so, this took me back to reflection - in and on practice (Schön). The minute by minute decisions and actions are things that over my years in practice have often saved me; and sometimes let me down big style. So really, the values of experience, and of implicit learning, cannot be overstated. The complex interactions in the classroom, and the way we work, which changes even as we are working, are key in our practice. So what? Well, so this blog, which is just my reflections - is a really useful one; I'm glad I've kept it up - the joint thinking and writing are key to my developing practice. (Image from Growth Coaching International, http://www.growthcoaching.com.au/articles-new/changing-the-lens-critical-reflection-through-coaching?country=au)

People who have worked with me or read any of my writing on reflection will know that I'm really keen on Stephen Brookfield's 'lenses' model for reflecting on teaching. he's recently updated his book so we have a 2017 version of the 1995 ideas, but really there is little difference. So I thought I would look for other models, so see if I am missing something new, or something that is useful. I found Terry Borton’s (1970) ideas - 3 stem questions: 'What?', 'So What?' and 'Now What?' that were developed by John Driscoll in 1994. Driscoll matched the 3 questions to the stages of an experiential learning cycle; and added trigger questions that can be used to complete the cycle. But this is old, and not very complex. Johns' model is based on five cue questions which enable you to break down your experience and reflect on the process and outcomes. John (1995) used seminal work by Carper (1978) as the basis for his model exploring aesthetics, personal knowing, ethics and empirics and then encouraging the reflective practitioner to explore how this has changed and improved their practice. But this is really designed with nursing practitioners in mind, and I am not sure that it really works too well for teaching? Tom Russell (2013) wrote a reflective article looking back on 35 years as teacher educator, and suggests that teacher educators rarely model reflective practice, fail to link reflection clearly and directly to professional learning, and rarely explain what they mean by reflection, with the result that student teachers may complete their initial teacher education with "a muddled and negative view of what reflection is and how it might contribute to their professional learning". (p.88) To be honest, in my role as external examiner I have seen this - trainees encouraged to reflect on their practice, but often offered no more of a structure with which to do this than 'reflection in and on action' which is really not much use in this context. For Russell, the problems relating to reflective practice result from the fact that teacher educators have not sufficiently explored how theories of reflective practice relate to their own teaching, and so have not made the necessary "paradigmatic changes" themselves which they expect their students to make. I would agree; it's lip service only, very often, that I see. And this can result in unhelpful and not very interesting egocentric descriptions of practice. Do we need to be constrained by existing models? Well, maybe not. But we do need a starting point. So after a bit of literature search, I think I would still go with Brookfield as far as my own and my students' practice goes. References Borton, T. (1970). Reach Touch and Teach, London: Hutchinson cited in Jasper, M. (2003) Beginning Reflective Practice, Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes. Brookfield, S. (1995) Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco Driscoll J. (1994) Reflective practice for practise. Senior Nurse. Vol.13 Jan/Feb. 47 -50 Johns, C. (1995). Framing learning through reflection within Carper’s fundamental ways of knowing in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 22, 2, 226-234 Russell, T. (2013) 'Has Reflective Practice Done More Harm than Good in Teacher Education?' Phronesis, 2(1), pp. 80-88 |

About me...

I was a psychology and social sciences teacher for many years and now I am in the throes of a leadership, teaching and research career in HE. I care passionately about education. This blog will show you why and how.

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed